The main stream western media regularly depict the conflict in Afghanistan as a relatively straightforward, bipolar confrontation between, on the one side, NATO forces supporting the Afghan President Karzai's government and, on the other, Taliban insurgents. In this model, Pakistan is presented virtually as an interested party looking on from the outside. This post, however, argues that although such an analysis might have held good at the onset of the conflict, currently it is a gross over-simplification, a misreading of events which gives a distorted view of the conflict by failing to identify accurately its true nature. It is rather, the post argues, a four-way conflict involving: NATO's ISAF and the Taliban; the Afghan government and the Taliban; Pakistan and the Taliban; and the USA and al Qaeda.

It is now beginning to look as if events in Afghanistan might be moving towards some sort of political end game. That is not so say that the military conflicts are over, or that the end game, when it comes, will be a definitive settlement. Far from it, but rather than a strategic end in themselves, the current conflicts are beginning to look to be part of tactics intended to establish political advantages in whatever negotiations will take place, perhaps most significantly the forthcoming Afghanistan jirga. Both NATO's and the Taliban's strategies seem to have changed to take account of this possibility.

There is little doubt, despite the way it has been widely reported, that during the summer NATO's ISAF inflicted a military defeat on the Taliban. The much-criticised British strategy of siting troops in Platoon Houses paid handsome dividends. In effect, it was sending a message to the Taliban along the lines of: if you want us out, then come and try to shift us. They came, they tried and, in some ferocious battles, they failed. At times it was a close run affair, not through the performance of British servicemen but through their lack of equipment and inadequate numbers, which remains the fault of the politicians in government. The Taliban have now eschewed frontal attacks in favour of random suicide bombings, which is not sustainable indefinitely, only as long as commanders have sufficient numbers of individuals low on intelligence and high on explosive. Despite the lethal dangers, it represents a tactical, rather than strategic, threat. NATO 's focus has now moved to reconstruction and passing responsibility for security to the Afghan army, as evidenced by Operation OQAB. In effect, NATO is trying to take a step back from military conflict into a support role. Not the least advantages of such an approach is to help give the Afghan government credibility in the eyes of its citizens. In effect the fortunes of NATO in Afghanistan is increasingly being tied to the performance of President Karzai's government on security.

The Afghan government itself remains something of an enigma. As yet, it has been happy to accept NATO's assistance in dealing with the Taliban but, given the levels of support for the Taliban within the local population, it remains to be seen how they will approach tackling the terrorists themselves. For the government to launch full scale assault against them would amount to a declaration of civil war and it remains to be seen if they are willing to take such a step, if it became necessary. First indications are that the politicians would be reluctant, hence President Karai's summoning of the jirga, in an attempt, whatever the rhetoric, to negotiate with the Taliban. We shall have to wait and see what develops in that line. For the present, it remains an unknown factor but there must be a worry that some tribal elders might prefer peace under the Taliban to even more years of civil war.

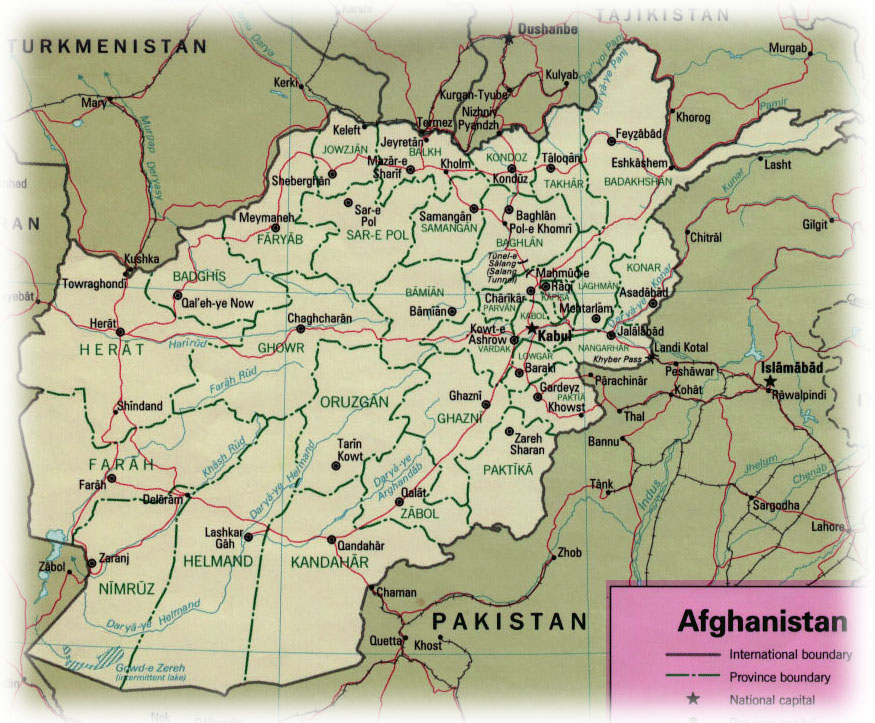

Paradoxically, despite the military defeat in Afghanistan, the Taliban are probably now in a stronger strategic position than at any time in their history. They now have what is effectively becoming their own state, or states, along Afghanistan's eastern border, stretching from Balochistan in the south, northwards through Waziristan and into parts of North West Frontier Province. This entire area could well be known as "Talibanstan", a term which, reports indicate, has some not entirely jocular currency in parts of it. "Talibanstan" is supposed to be Pakistani sovereign territory but, after suffering a military defeat at the hands of the Taliban in Waziristan, the Pakistani government's writ no longer runs in these lands. Indeed, at the best of times the various indigenous tribes are fiercely independent and not receptive to outside control from Islamabad or anywhere else. This places Pakistani President General Musharraf in a bind. On the one hand, he would probably like to regain control of the areas and he has no sympathy for Islamic extremists, who are a destabilising influence throughout his country. On the other, having suffered heavy casualties the last time the Pakistan army took on the Taliban, the generals are in no mood to try again. Moreover, he has potential problems with Islamic extremists, sympathetic to the Taliban, within the army and ISI (Intelligence Services). Musharraf is negotiating his attendance at the Afghan jirga, so he is unlikely to make any moves in the immediate future. but his priority will almost certainly be surviving his own domestic problems, even if that means again surrendering to the Taliban on some issues. The last thing the Coalition needs is for its reliable ally to be replaced by a new president who may feel he has to consolidate his position by making significant gestures towards Pakistan's Islamic extremists, some of which could be be at NATO's expense.

A fourth, generally un-remarked aspect to the war is the USA's hunt for Osama bin Laden and his senior al Qaeda commanders. There is little doubt that they are holed up in the tribal lands, the area around Bajour, scene of yesterday's missile attack on a madrassa. However, misssile attacks are unlikely to succeed since al Qaeda probably has enough well-placed friends in the ISI, if not the army, to receive advance warning. All the Bajour attack achieved was to strengthen the Taliban's influence in the area and to weaken Musharraf's position.

For now, all we can say with confidence is that, so far, the Coalition operations in Afghanistan have been a success. Although, as ever, the future is unpredictable we can say with some confidence that, in the political manoeuvrings of the endgame, neither the Afghan nor the Pakistani governments are natural allies of the Taliban. The difficulty facing NATO now is how exploit their military victory in order to politically strengthen both presidents against the terrorists.